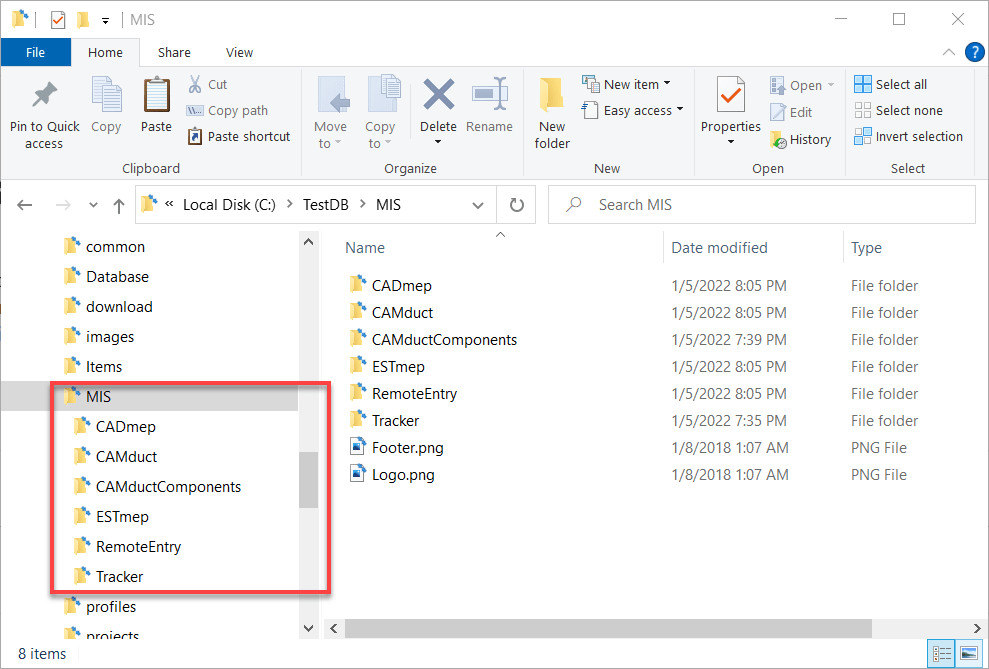

Those of you who used CADmep, CAMduct or ESTmep prior to it’s acquisition by Autodesk remember when all the reports were in one folder. Once Autodesk took over, they moved to a system where each product used a separate subfolder for their reports. After all, ESTmep is likely using different reports than CADmep and yet different than CAMduct. Here’s what your configured reports folders now look like (you may not have all products/folders). Notice how each product has it’s own older.

The reality is, many reports are helpful across products. This means you need to make the same report multiple times or copy it from one folder to the others. This leads to duplication of data and a chance than one of the copies gets changed different from the others.

Consolidating All Report to a Single Folder

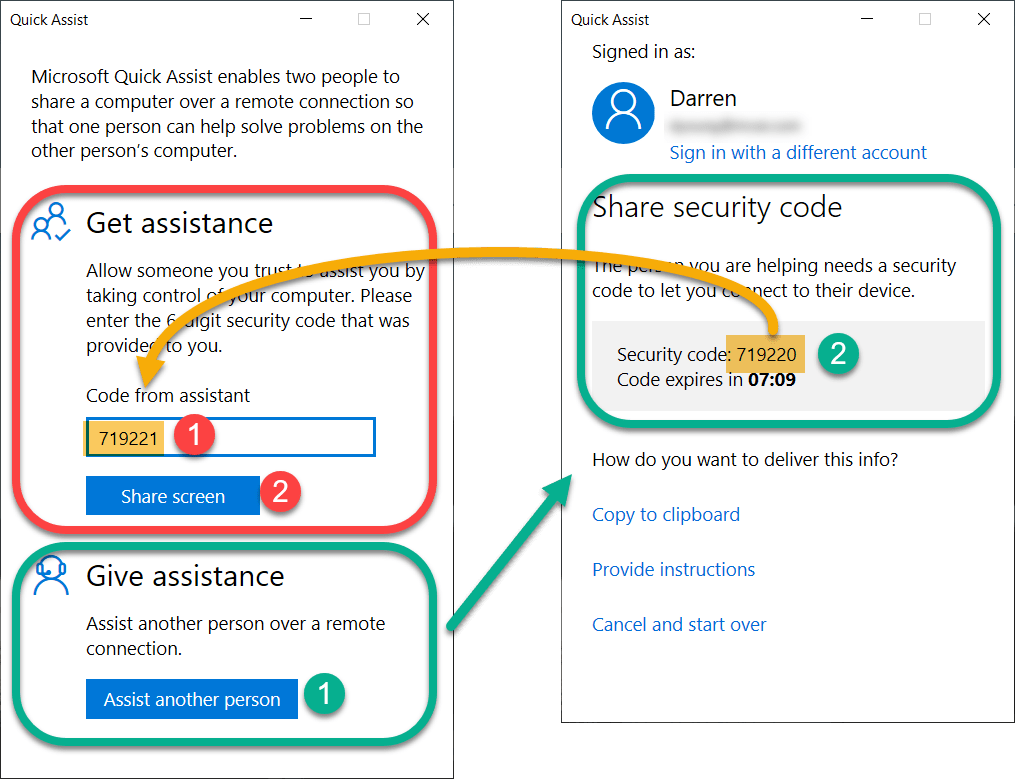

It’s commonly asked if it’s possible to configure the different Fabrication product to use the same folder. The answer you always hear is No. Technically that’s correct. You can’t configure Fabrication products to look at the same folder. However….

You CAN configure Windows to make multiple folders look at the same folder. It’s just done at the Windows level with a feature called Junction Links.

So lets walk through how to configure CADmep, CAMDuct and ESTmep to all look at the same reports.

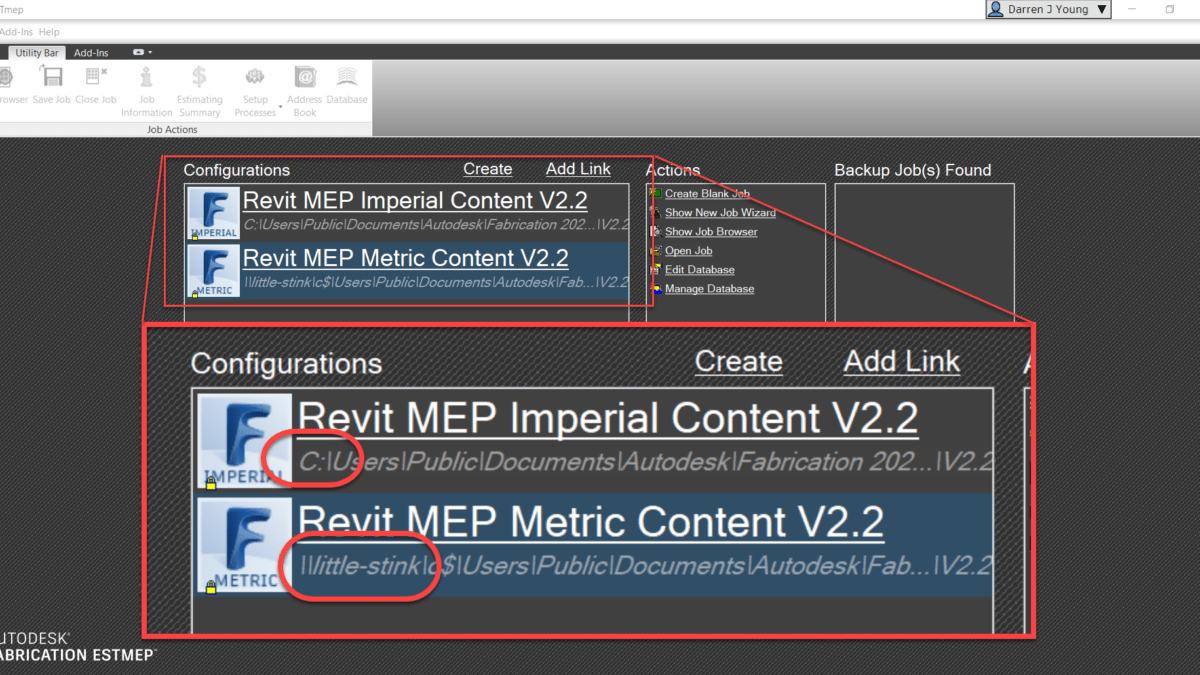

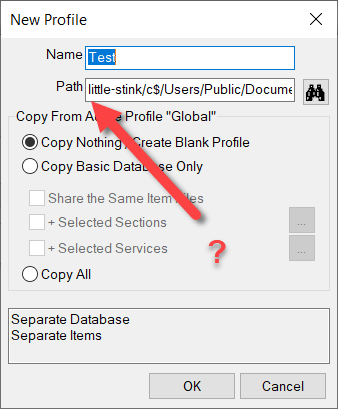

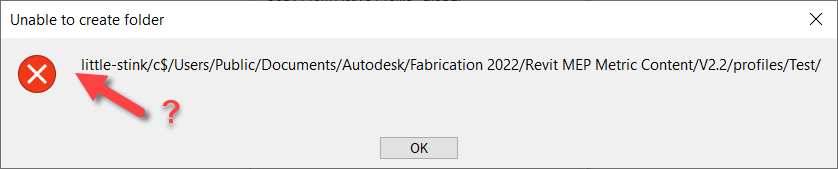

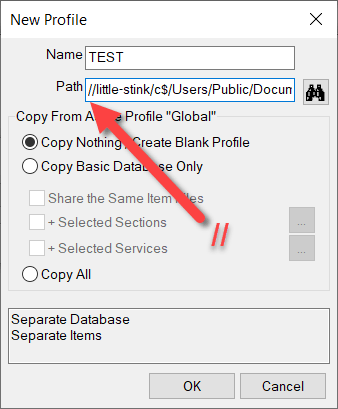

Step 1: Find Where Your Reports Are Located

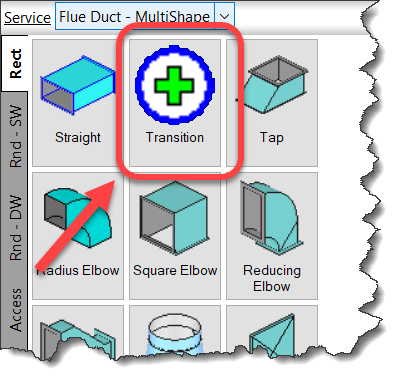

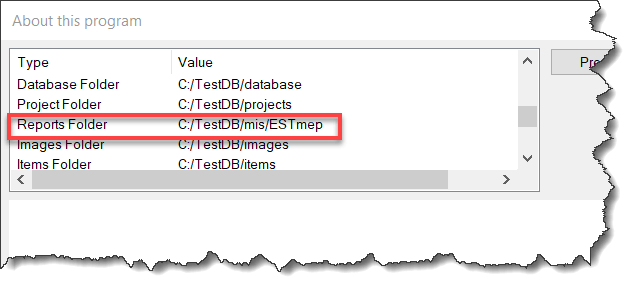

Using CAMduct or ESTmep you can pick Help -> About or type AppInfo at the command line in CADmep. You can then scroll through the window to see where the Reports are located. Alternatively, you could use the Edit Configuration utility to find this folder as well.

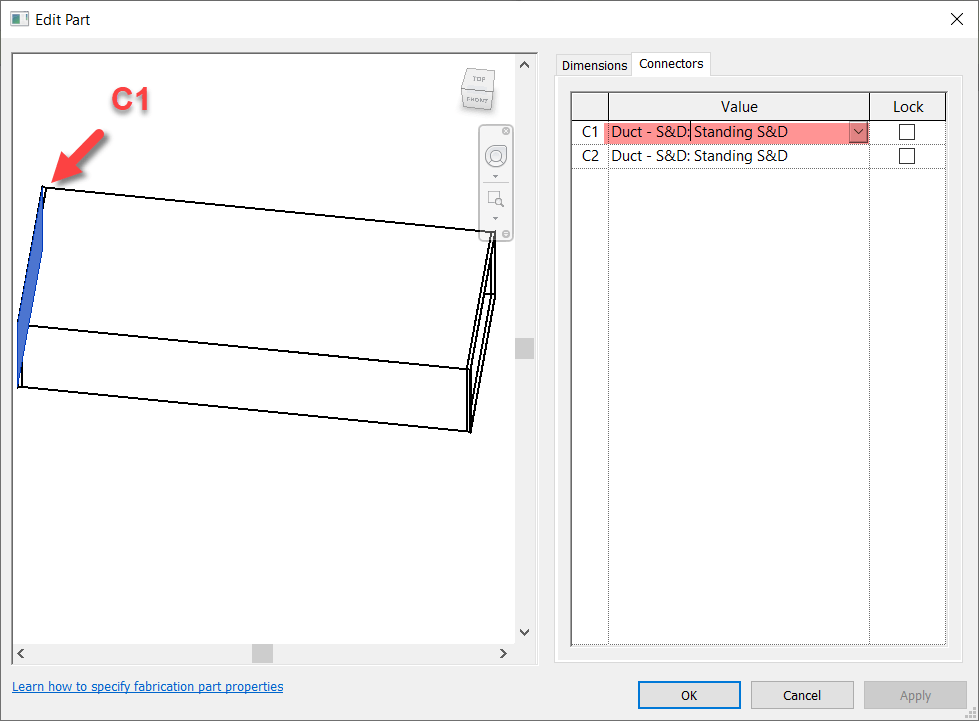

Note that this screencap was done in ESTmep so you see the ESTmep subfolder. The mis folder is actually the root where all your reports are.

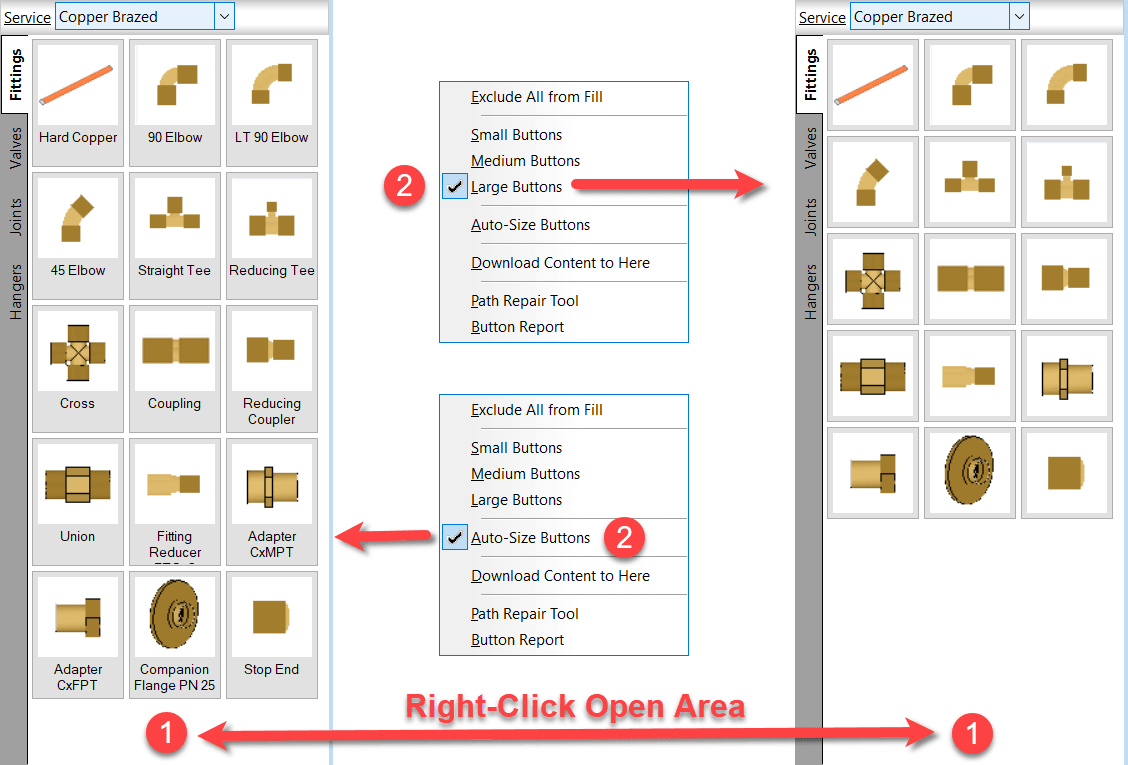

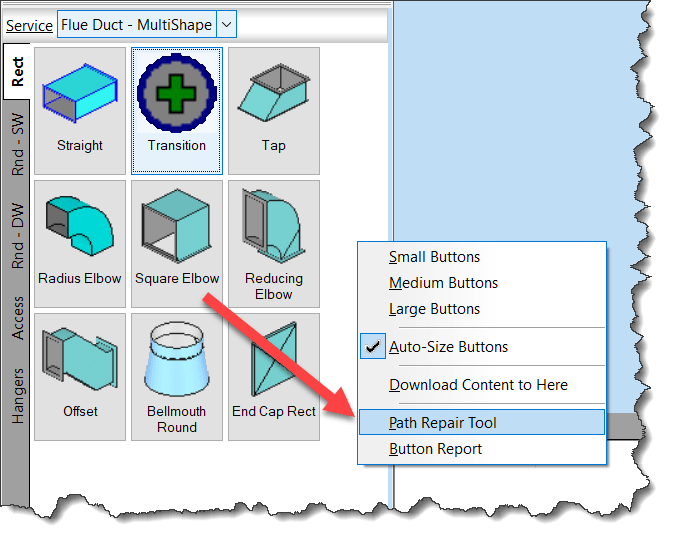

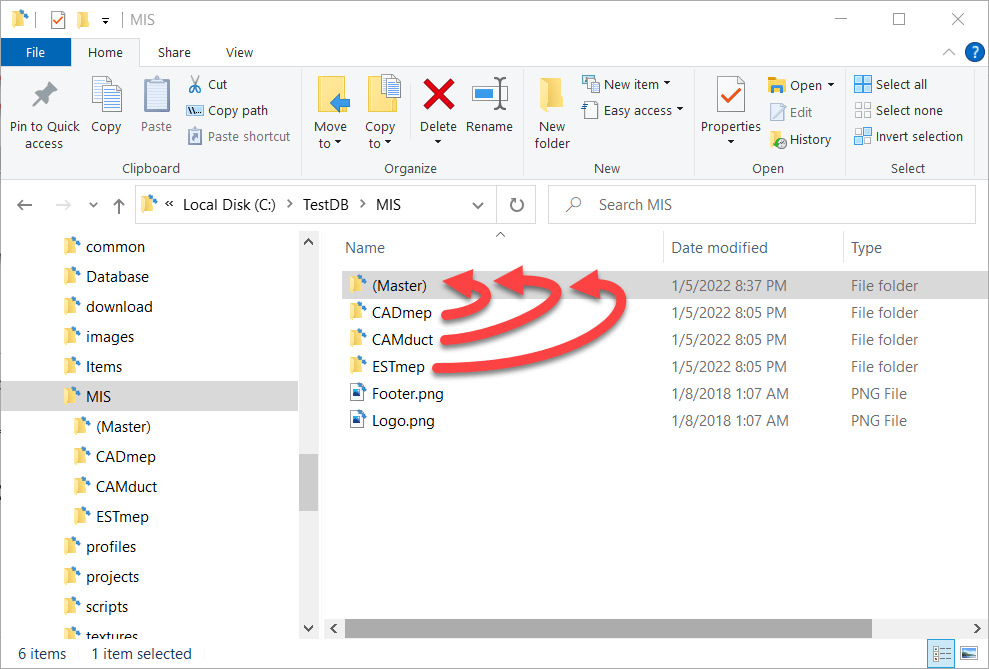

Step 2: Copy All Report Folders to a New Folder

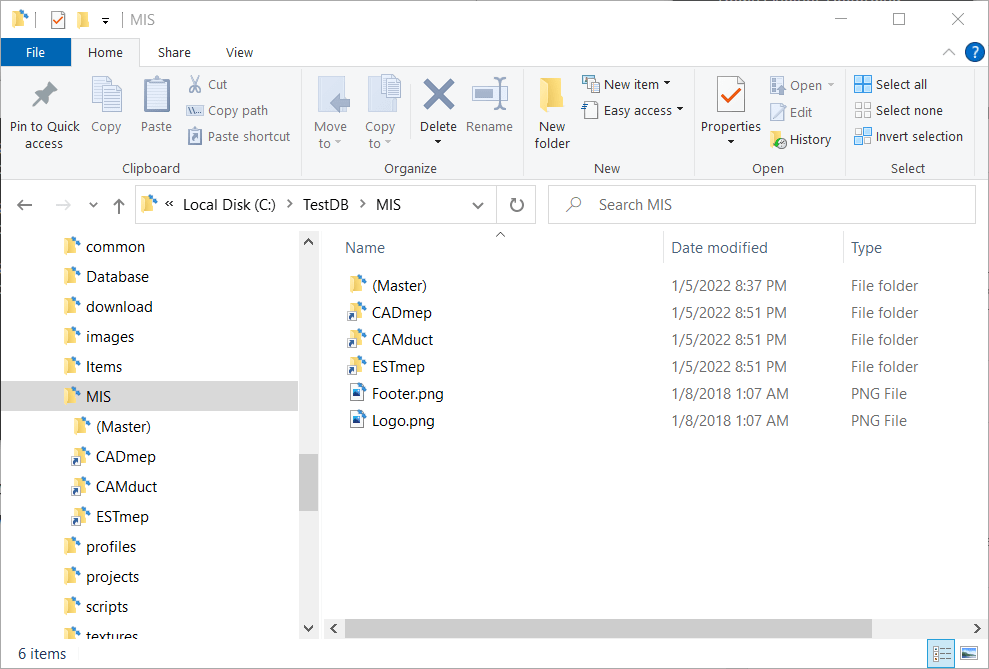

The next step is to copy all the reports from the various product specific folders to a new master folder location to store the reports. In this case, we’ll call it (Master) just to make it super obvious. Notice we also deleted the folders for CAMductComponents, Tracker and RemoteEntry because I’m not using them. You can choose to include them if you need them,

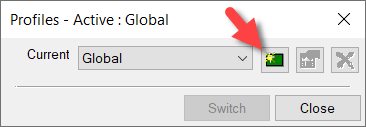

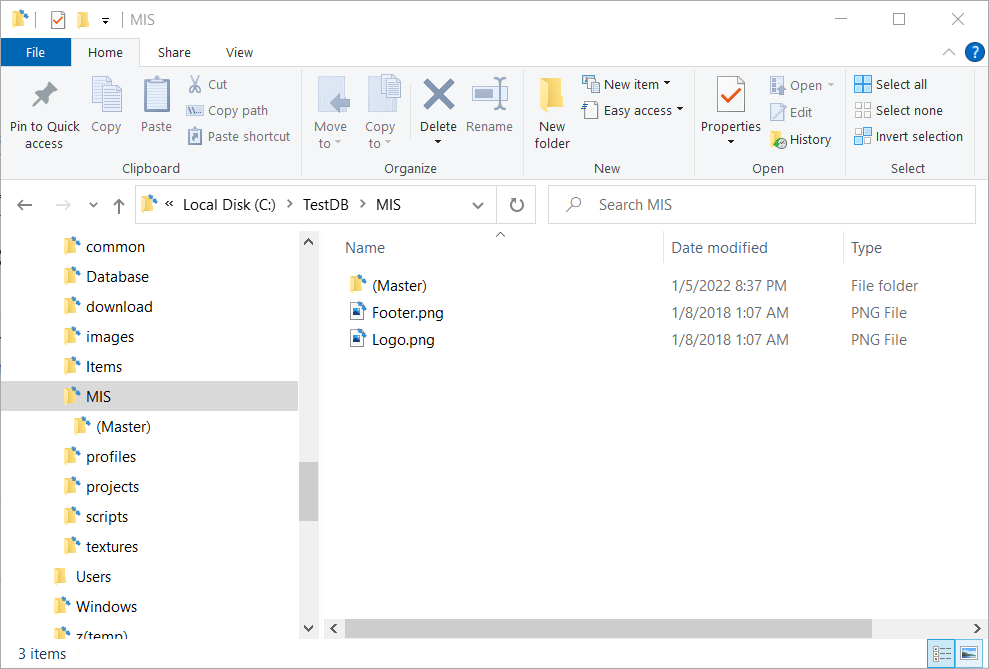

Step 3: Backup and Delete the Original Reports Folders

When you’re done, you should back a backup of the product specific reports folders elsewhere incase you want to go back to the original config. Once backed up, you need to delete the original product specific reports folders. When you’re done, your reports folders will look like this…

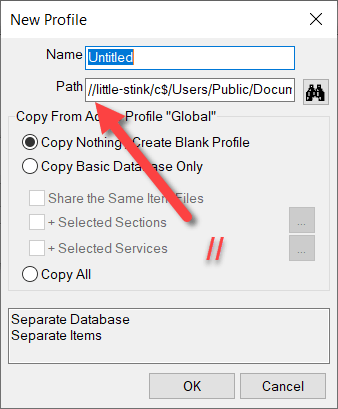

Step 4: Create Junction Links for the Product Folders

Here’s where we do the magic. Windows allows you to create what’s called a Junction to other folders. A Junction is just another virtual folder that looks at the contents of another. Junctions are how Windows has a “My Documents” folder that really points to “C:\Users\<Username>\Documents“.

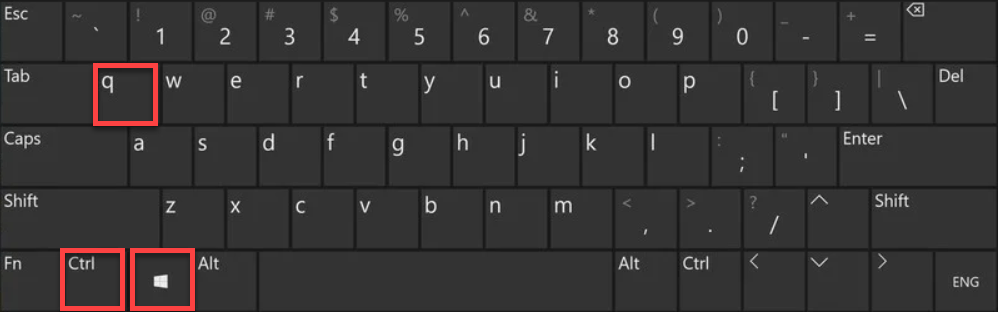

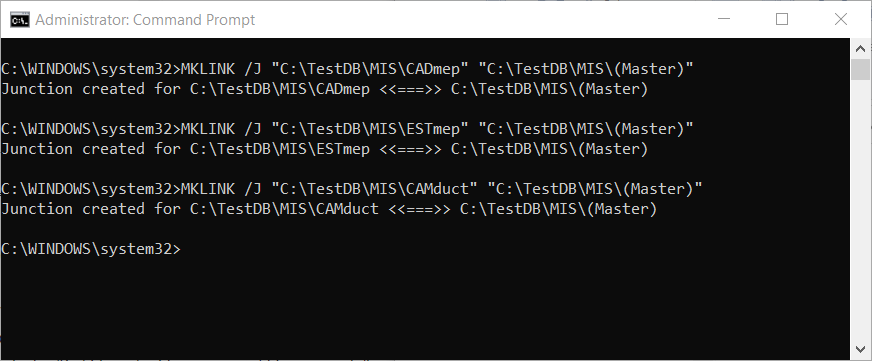

To create a Junction you need to open a Command Prompt with Administrative permissions. One that’s done, you use the MKLINK command to make a Junction Link to a Junction Target. The syntax looks something like this….

MKLINK /J "link folder" "target folder"Here’s a screencap of my DOS Command Window where I make Junction Links to the (Master) reports folder…

When done (if Successful) you’ll see those product specific folders again for CADmep, ESTmep and CAMduct. But this time, you’ll notice the icons are slightly different and look like a shortcut icon even though the folder acts like a regular folder.

Here you can see a side by side recording of the process happening in real time…

Step 5: Use Fabrication As Normal

Once you have the junctions created, you can use your products as normal. Each fabrication product looks to the folder specific to it, which Windows redirects to the file in the (Master) folder.

One thing to note, is that when browsing the (Master) and product specific folders, the only clue that these are Junction Links is the Shortcut looking arrow on the icon. If you don’t know what’s going on, it would appear that you have 4 folders each with the same files. But if you try to delete the files in one, they will indeed disappear from the other folders too. After all, these folders are Links back to the Target.

Here’s a recording of all 4 folders show at the same time. You’ll see that changes to any one also happen to the others. You may need to Refresh the views to see the changes but they indeed are seen from the Target and all Junction Links. This means that while there’s 4 folders showing the same files, they only take up the size on disk in one folder.

Summary

Junction Links work well for letting all (or some) of your Fabrication products use the same list of Reports. But there are a few noteworthy items to be aware of….

- Junctions Links and Point to Targets on a different DRIVE or FOLDER as long as it’s on the SAME machine. You can’t make a link to a target from a computer to a server for example.

- If you access your database from a network location, you need to make make the links from the server so your IT Department may need to get involved. Your local software when accessing the server share will honor the junctions it sees on the server.

- If you don’t know what’s going on or look closely, it appears you have duplicate data. Make sure you don’t delete things from one folder thinking they’ll still be in the others.

- If you want to undo this setup, you should delete the Junction Links FIRST just like any other folder before deleting the Target folder. If you delete the Target first, the you’ll have trouble deleting the links.

- IF you Sync your database from a master source location like Dropbox or using a utility like Robocopy, the Junctions are NOT copied, but are instead copied like regular folders. There may be some special utilities that copy the junctions but I’ve not found them. So what is 4 views of 1 copy of a file on a network, when synced to your local system becomes 4 copies of the files in 4 folders. For the most part, it’s not an issue as you manage from the master source location. None the less, this nuance is worth mentioning. Most Sync utilities do NOT recognize the special nature of a junction and treat them just like a folder.

- If you want to read more about Junction Links check out this article…https://www.addictivetips.com/windows-tips/create-delete-a-junction-link-on-windows-10/