Defensive Driving for Coders

Disclaimer: I’m not a professional coder. Just a good hack, script kiddie, amateur, whatever you want to call me. But I’ve been doing it for a while and I tend to be good at finding ways to make things less error prone. I also pickup tricks from industry peers who humble me with their ability.

If you aren’t a professional programmer, you’ve likely never been told either. So I’m telling you as its helped me and I’m sure it’ll help you too if you’re an amateur like me.

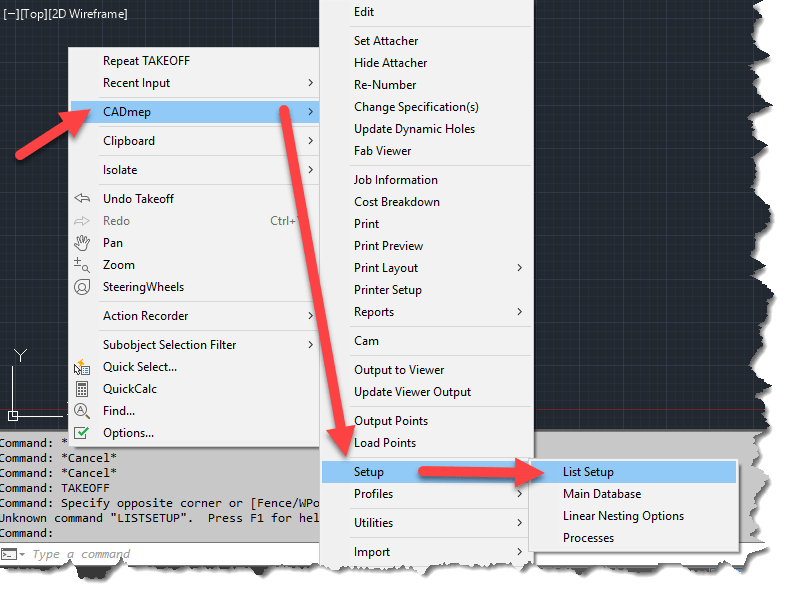

This works regardless of language. Whether you code in Visual Basic, AutoLISP, Java, C# or any other language the concepts are the same but the syntax will be different. For this reason, I’ll use pseudo code…that is, syntax that isn’t any particular language but uses terms obvious to describe what’s going on.

The Issue with Strings (Text)

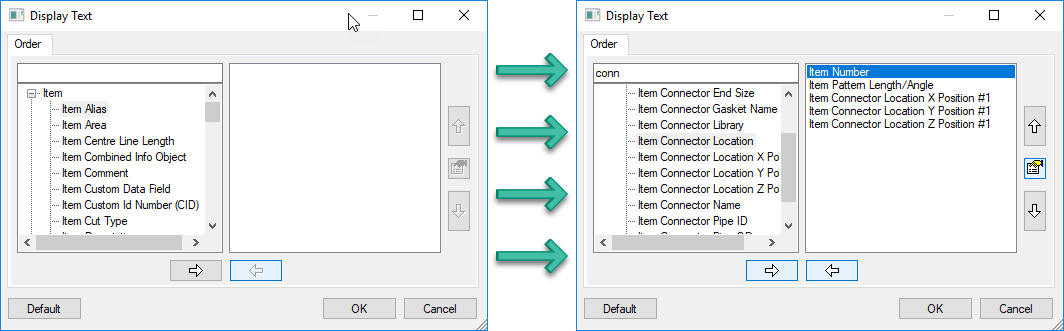

A common activity in any programming is reading text, often called String data types. You read the value from somewhere else like a property or have the user type the data. You then need to test the data in a conditional statement to see if the data is valid. You may also be testing to see which action to take depending on what was typed.

The problem when doing this is you don’t always know the case used when typing. Most conditional testing on string data is CaSe SeNsItIvE. Take the following examples….

MyValue = "Elephant"

if MyValue = "Elephant" then

MessageBox "Yes - There's an Elephant in the room"

end if

This code works because the case of the text strings is identical. But what about this….

MyValue = "elephant"

if MyValue = "Elephant" then

MessageBox "Yes - There's an Elephant in the room"

end if

In the above code, the test fails because the “E” in “Elephant” is now lower case. This is very simple to solve and is obvious once it’s pointed out.

To resolve this, when you test a String value, use code to force the value to either UPPER (or lower) case and test against that. Now look at the following code…

MyValue = "Elephant"

if Upper(MyValue) = "ELEPHANT" then

MessageBox "Yes - There's an Elephant in the room"

end if

…or this example….

MyValue = "Elephant"

if Lower(MyValue) = "elephant" then

MessageBox "Yes - There's an Elephant in the room"

end if

In either of these examples, we take the value we want to test, force it’s case one way or the other and test against that case. Now it doesn’t matter what case is typed by a user or returned when reading a value, the test is now essentially inoculated from case differences by forcing it one direction or the other.

A Less Obvious (but related) Tip

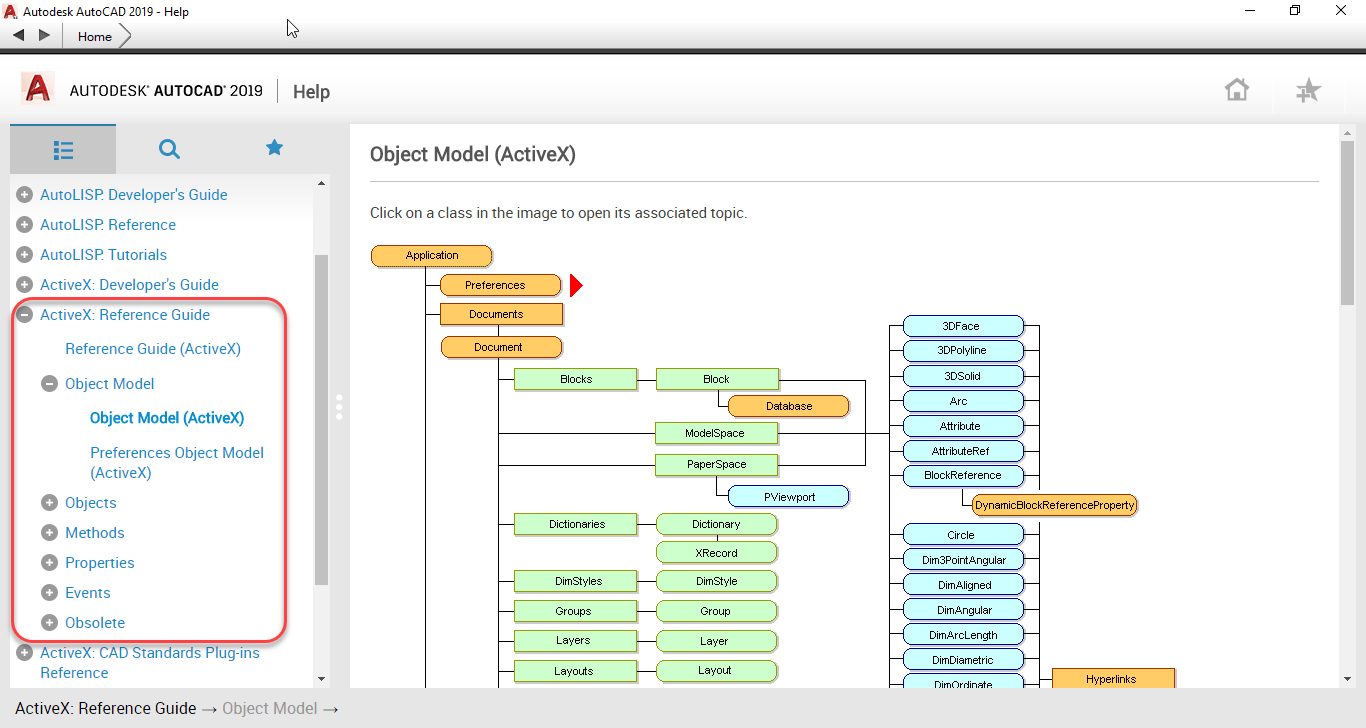

Another common mistake I see people do is not use this technique when they know the software better. For example, lets say you wanted to retrieve the type of AutoCAD object and noticed that AutoCAD ALWAYS returns the name in mixed case….”Line”.

It’s common for less experienced programmers but very smart and observant coders to ignore the tip I just suggested. I’d advise you to NOT do that…always use a forced case when testing text strings. Even when you’re sure the value you are reading and testing is always a particular way.

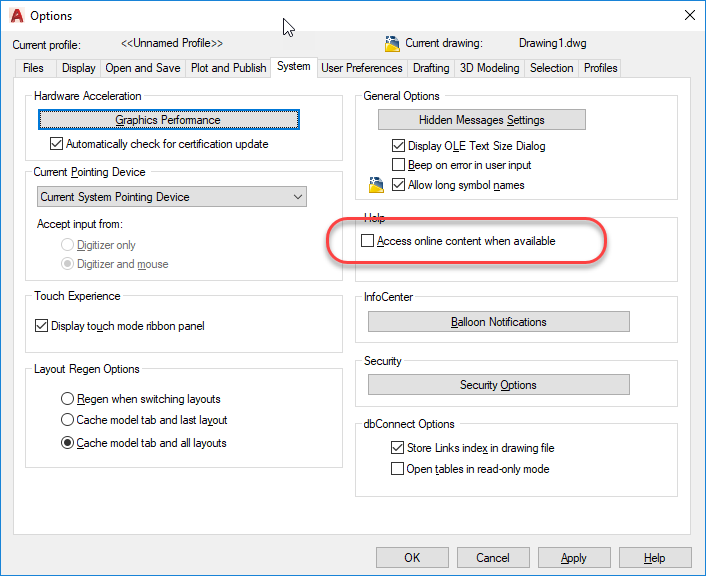

Why? What happens if…that pesky if…AutoCAD or whatever you are using changes? Autodesk sees a lot of programmers…maybe they overhaul AutoCAD code and object types are now returned upper or lower or a mix? You’ve now put in the hands of someone else if your program will break in the future. As unlikely as it seems, it’ll eventually happen. The key to writing resilient code is tricks like this. Think of it as a coder’s version of “Defensive Driving”. Anticipating future inconsistencies and planning for them makes your code more resilient and less likely to break on your next upgrade.